Christmas is over and the days are slowly getting longer. This year I have decided to try to sow earlier some of my vegetable and flower seeds indoors, provided that I can get some supplementary lighting to stop them becoming ‘leggy’. This has meant doing a bit of research on LED plant growth lights. In the past they have promised great savings in energy costs but their prices has been prohibitive. It now appears that I can buy one for under a tenner.

The problem is that the choice is huge with differences in the balance of the blue and red light emitted. As a rule of thumb, the red part of the light spectrum is good for encouraging growth and flowering and the blue part is good for producing sturdy plants. Interestingly some emit a balance of light that is claimed to be equivalent to sunlight received at 10.00 a.m. (I assume GMT). This claim interested me because a couple of years ago I said in a blog on the reasons for high yields in 2015 that research suggests that morning sunshine is used more efficiently by wheat than sunlight later in the day. I have been digging around in the literature but have been unable to find any research findings on the implications on wheat of the spectrum of the light produced by morning sunlight.

Whilst searching the scientific literature, I discovered that the photosynthetic efficiency of wheat is influenced by the co?ordination between supply (photosynthesis) and demand (sink size; during grain fill this is mainly the number of grains and their rate of growth). In general, photosynthetic rate declines when sinks are reduced but increases when sinks are increased (i.e. demand increases) (full details). Hence, high yielding crops use solar radiation more efficiently and this contributes to a more efficient use of nitrogen. In addition, the efficiency of use of solar radiation also partly depends on its daily distribution. It is better to have six hours sunshine every day rather than 12 hours sunshine every other day (full details).

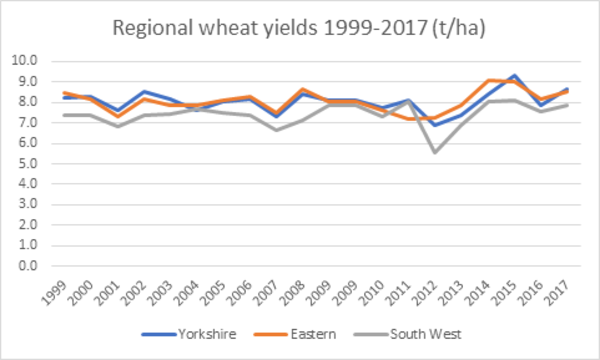

Such variations in the exploitation of solar radiation by wheat help to explain why predicting yield is a fool’s exercise. Throw in the fact that other factors, such as soil moisture supply, can significantly influence yields only compounds the madness. Simple and fixed conversion rates of solar radiation to crop growth and yield can lead to significant errors in prediction. For example, using these simple and fixed conversion rates suggests that the South West should have the highest wheat yields but in fact Defra Statistics show that it is one of the lowest yielding areas in the UK.

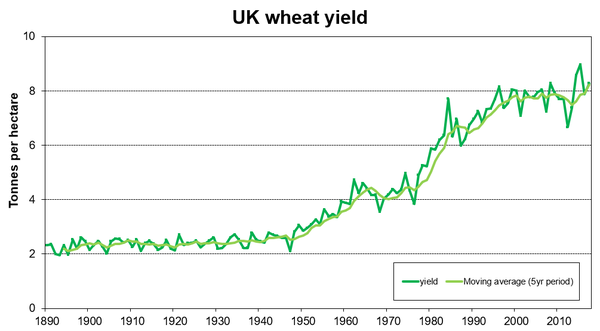

Returning to my madness…. I have been attempting to predict yields in a July blog for the past few years. How did I get on this year? I concluded in a mid-July blog (uploaded on 14 July 2017) that ‘I think that in many parts of the country the wheat yields will do well to be above average. Second wheats seem to have particularly suffered from the lack of rainfall. However, yields in Lincolnshire and further North may be more pleasing’. Hence you can imagine my surprise when in early October Defra estimated that the UK yield was well above average at 8.5 tonnes/hectare. However, its final estimate published on 21 December is 8.3 tonnes/ha both for England and the UK. This is just above the 2013-2017 average of 8.2 tonnes/ha but well above the 2012-2017 average of 8.0 tonnes/ha. As you know 2012 was a low yielding year and including it lowers the average. This demonstrates how news stories can be manipulated by the choice of the comparators.

Therefore, I slightly under-estimated the yields in areas where there was a significant early spring drought. Dry springs are generally good for yields, partly because they are typically associated with above average solar radiation. This year the drought was severe enough and long enough for me to be concerned about its negative effects on average yields. However, wheat yields did suffer on light soils in some areas. My other concern was the warm spring and early summer that accelerated growth and development. This meant that there were fewer days than average for the crop to intercept solar radiation but I hoped that the above average levels of solar radiation during this time period would largely balance this out. It seems it did. Finally, there was concern about the blistering temperatures over a couple of days in late June but it seems that this was sufficiently far enough after flowering to have little effect.

In terms of regions, perhaps I was correct in predicting well above average yields for the North East and Yorkshire and The Humber.

One final observation. The graph below from Defra statistics indicates that after a 20-year plateau the five year moving average wheat yield is now rising. However, a repeat in 2018 of the conditions endured in 2012 may wreck this optimism. Let us hope for a good 2018 harvest.