I made a big mistake at the end of a recent blog when I mentioned that we could soon expect to cultivate GM glyphosate tolerant oilseed rape. This optimism chimed with recent reports stating that we could soon grow waves of GM crops now that the EU has signed a new law on the cultivation of them. This law enables member states to opt out of or ban authorised GM crops. This means that decisions to allow cultivation of authorised GMs will be taken by member states rather than seeking a seemingly impossible ideal to achieve pan-EU decisions to cultivate such crops.

The hope is that this will encourage the EU Commission to bring forward votes on applications for GM crop cultivation; some applications have been stuck in the system for more than a decade.

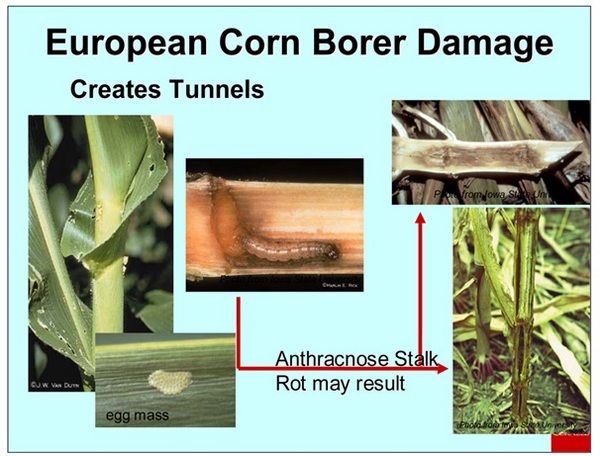

However, many applications for cultivation were withdrawn some time ago. These include applications to cultivate blight-resistant potatoes, GM high starch potatoes and glyphosate-tolerant beet. It appears that there is no glyphosate tolerant oilseed rape in the EU approval system. What remains in the system is Bt (insect resistant) and herbicide tolerant maize. Currently corn borers, the target for BT maize, have limited distribution in the UK. These insect pests damage the stems (see image) and cobs of maize and increase the risk of mycotoxins in the grain. Whilst there are no major weed control problems in UK maize production, the ability to use glyphosate may reduce overall growing costs and it will certainly ease the management of the crop. In addition, with sympathetic management, glyphosate tolerant maize may enable the introduction of some biodiversity into a crop that has currently very low levels.

So what of the wave of new GM crops? It is arguable whether it is worth the companies going through the registration costs to get EU approval to cultivate GM crops if there are only a handful of countries in the EU minded to allow them to be sown. The regulations are unnecessarily complex, expensive and restrictive and I suppose we will have to wait and see what happens. In the meantime, we will slip further behind the rest of the world in producing food more efficiently whilst minimising environmental impact.

Perhaps of equal concern is the queue of animal feed crops containing the more recently introduced GM developments awaiting approval for import into the EU. There is always a natural slow down in decision making when an EU commission approaches the end of its tenure and a new one starts up. However, there have been no such approvals in the last year. Recently, Juncker, the new president of the EU commission, has asked for a review of decision-making on GMOs which will further exacerbate the problem. Nobody yet knows the full repercussions of the review but an announcement to clarify its scope is expected over the next month or two. In the meantime, it is unlikely that new import approvals will be made. This means that the supply of imported maize and soya will become ever more restricted.

It is hard to understand how such a situation has developed where emotion rather than facts and a mentality lacking in ambition and vision has blanketed the debate on agriculture in Europe. I realise that some lobby groups and individuals have benefited from their anti-GM and anti-pesticide stance but it clear to me that this is an indication of a wider malaise in Europe. I suppose in the end, the rest of the world will demonstrate what we are missing. In the meantime, Europe will increasingly have to rely on the rest of the world for its food supplies. Inevitably, this anti-science attitude will lead to higher food prices. This may not be so bad for European consumers but it could be devastating for those in the less developed parts of the world. But hey-ho, the debate on GM and pesticides in Europe has always been based on the “I’m alright, Jack” mentality.

Picture by Cornell University