I have recently taken a renewed interest in which nozzles farmers fit to their sprayers. On the heavy soils in East Anglia the vast majority regularly use Air Induction nozzles to reduce spray drift but when I asked the question in the Cotswolds recently, the vast majority of farmers didn’t use these nozzles. The explanation for this difference is clear; LERAP (Local Environmental Risk Assessments for Pesticides). This was introduced in 1999 to prevent short-term shocks to aquatic life caused by spray drift; there aren’t many water bodies and drainage ditches to protect in the Cotswolds. This, I must admit, rather folksy tale demonstrates that the original LERAP scheme was a classic case of farmers being rewarded for good practice.

The scheme enabled, for many pesticide products, those who fitted nozzles which decreased spray drift to reduce drastically the width of the aquatic buffer zone of 5-metres alongside water bodies, including ditches. It also recognised that as dose (as a proportion of the label recommended dose) decreased and the size of the water body increased, reductions in the buffer zone could also be adopted. This sounds complex but the look-up tables were easy to understand and the scheme was relatively easy to adopt. It’s a pity that the original explanatory leaflet made it sound more complex than it actually was!

However, the recent EU pesticide regulations have significantly increased standards i.e. there is now less tolerance of spray drift to aquatic ecosystems.

It became clear to the pesticide manufacturers that sticking to a maximum buffer zone of just 5-metres could mean that many existing pesticide products would not get through the 10-yearly re-registration process. So in 2011 CRD agreed to introduce interim arrangements that extended buffer zones up to 20-metres.

What surprised me and many others was that there was no flexibility to reduce buffer zones of between 6 and 20-metres through good spray practice, dose reductions or because of the increasing size of the water body.

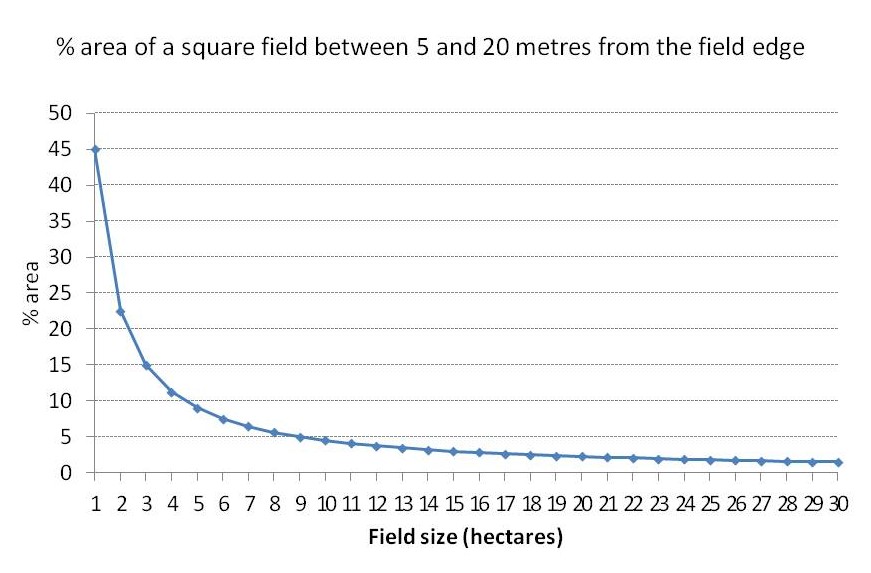

I have calculated the percentage area of a square field that falls between 5 and 20 metres from the field edge. I recognise that this is rather simplistic and assumes a buffer strip on all four sides; typically, the yield losses due to hedges and field side vegetation do not extend beyond 5 or 6 metres into the field and so the loss of area will directly reflect the loss of production.

The figure demonstrates that it’s those farmers with small fields who will be more penalised. Some retained smaller fields to retain landscape features and biodiversity, so it seems that, in those respects, good practice is being penalised by these interim arrangements.

A brief review of recently issued authorisations for new products or re-registered products shows that wider aquatic buffer zones will be appearing on new labels. There is a pendimethalin product with a 20-metre buffer zone and straight diflufenican has a 12-metre buffer zone.

This is more than a little worrying because complex tank mixes, often containing these two herbicides, have to be adopted for black-grass control in the autumn. The time of application means that there is more likely to be water in ditches.

There are some other recently authorised products that have significantly wider buffer zones than the ‘old’ 5-metres. This demonstrates that with today’s necessity to tank-mix in order to get the job done, there is a potential for farmers to be forced into wider buffer zones or to use a more limited range of chemistry to control weeds, insects and diseases; the latter will only increase the risk of resistance developing.

So I hope that the ‘powers-that-be’ can develop ways of encouraging good spray practice in order that these wider buffer zones can be reduced whilst still meeting the higher standards set by the recently introduced regulations.

By the way, notice my use of language. Just to remind you that nowadays active ingredients are ‘approved’ and products are ‘authorised’.