We now have a few new registrations coming through that have been completed since the HSE’s Chemicals Regulation Directorate (CRD) introduced its interim arrangements on assessing aquatic buffer zones.

The new product Teridox (dimethachlor) has a buffer zone requirement of 10-metres and the new Hurricane (diflufenican) labels will have a buffer zone requirement of 12-metres. Dow claims that Dursban (chlorpyrifos) would require a 72-metre buffer zone according to the method of assessment that’s being used under the interim measures. Under the interim arrangements buffer zones wider than 5-metres cannot be reduced under any circumstances, but they are only necessary when there is water in the ditch.

These are worrying buffer zone widths and all kinds of issues arise from this situation.

First of all, are the new widths based on good science? I know that the basic drift model used to develop the original LERAPs scheme was based on a narrow boom width sprayer travelling slowly. Drift from sprayers travelling at 12-14 kph is undoubtedly higher. So there may be some logic in the wider buffer zones from that point of view. But the question has to be, has something been identified that suggests that current buffer zones and application techniques are causing a problem?

The only information I can find on the likely scale of any problem is dated 2010 and says that only 1% of surface water bodies monitored by The Environment Agency are failing their Environmental Quality Standards for pesticides. This is a low level of failure, but of course any failure has to be regretted. However, a failure may have been due to pesticides moving to water through the soil or on the soil surface rather than spray drift.

Monitored water-bodies tend to be lakes and rivers and not small ditches on farms. So the question is whether farm ditches, which may have water in them from time to time during the year, contain a viable aquatic ecosystem that requires an aquatic buffer zone to protect them? The French authorities appear to be of the opinion that this is only seen with larger on-farm streams and water-bodies.

Monitored water-bodies tend to be lakes and rivers and not small ditches on farms. So the question is whether farm ditches, which may have water in them from time to time during the year, contain a viable aquatic ecosystem that requires an aquatic buffer zone to protect them? The French authorities appear to be of the opinion that this is only seen with larger on-farm streams and water-bodies.

The other issue is whether mitigation will eventually be introduced so that these newly introduced buffer zones that are wider than 5-metres can be reduced in the future. Let us hope so. The great thing about the original LERAPs scheme was that it rewarded good practice by allowing a reduction in buffer zone width due to the adoption of lower doses and/or reduced drift spraying techniques. This resulted in many farmers using the lower drift air induction nozzles for nearly all spraying operations and there are now other engineering solutions that could further reduce drift, including improved control of boom height. Let us hope that good practice will eventually be rewarded when the arrangements are finalised.

There are other mitigation methods that also need to be investigated. Drift studies are carried out where there is very short vegetation, but there is some evidence that taller vegetation in the buffer will trap a very significant amount of drift. This also offers the opportunity for a bit of joined-up thinking because such vegetation, correctly managed, may also be a large step forward for biodiversity.

Some farmers think that one way forward would be to use adjuvants to reduce drift. This is a minefield as an adjuvant may reduce the drift for one product but may increase it for another; the ultimate minefield would be when tank-mixes are used.

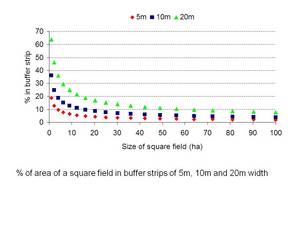

The graph shows the impact on land availability for food production of wider buffer zones. Paradoxically, it is those farmers who have ‘done the right thing’ for biodiversity who are the ones that will be most penalised because they haven’t created large fields by ‘piping-in’ ditches and removing hedges.

I recognise that this is the worst case scenario because I’ve assumed a buffer zone on every side of the field but you get the ‘drift’ (sorry about the pun). It is sobering fact to mention that our high yields mean that for every hectare of cereals not produced in this country a few hectares will have to be grown elsewhere in the world. It is beholden on us not to export environmental impacts to other countries.

There are other implications as well. Farmers, where they can, will avoid those products with wide buffer zones, and not just on the fields that have ditches that may have water in them at the time of application. This is because of the way that arable farming now has to work - spray operations are pre-planned and appropriate to not just one but a number of fields. Hence, there could be more reliance on fewer modes of action and an increase in the risk of pesticide resistance.

So, there’s a lot to play for and we look to the regulators to consult widely and to develop a simple but scientifically robust solution that meets the concerns of the farmer and the conservationist as well as the consumer who is reeling from higher food prices.