NIAB’s Nichola Hawkins explains all about her recent paper, published with fellow NIAB staff member Bart Fraaije and Isabel Corkley from ADAS:

The problem of antibiotic resistant infections in medicine has received increasing attention in recent years, but farmers and their advisors are all too familiar with resistance problems too.

Fungicides are a vital tool to control plant diseases, protecting yields and avoiding fungal contamination and food waste. But many key pathogens are evolving resistance to an increasing number of fungicide types.

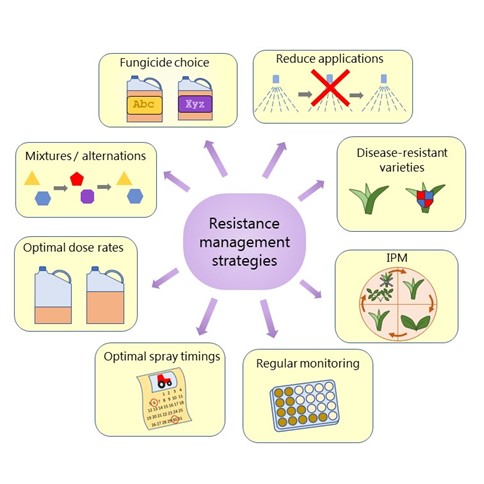

We have reviewed the latest scientific studies, from mathematical models to field trials, to see what the current evidence tells us would be the best management strategies to keep fungicides effective for as long as possible in the face of evolving pathogens.

Key recommendations

The over-riding principle is to spread the load, across different fungicide classes as well as combining chemical and non-chemical disease control measures. A single-site fungicide, used solo, on a susceptible variety in an intensive cropping system with no other control measures, will very quickly select for resistance. Mixing with another fungicide with a different mode of action, in combination with choosing a more resistant variety, will prevent any one control measure from breaking down so quickly.

Much of the advice that farmers know well hasn’t really changed, although the specific products have. For example, previous advice would have been to mix a strobilurin with an azole. Now the azoles are still in the mix, thanks to the development of newer more active compounds, but the mixing partner will be an SDHI or maybe now a QiI.

Changing views

In other cases, previously accepted advice may no longer match the evidence. Recommendations to always use products at full dose would be more suitable where partial resistance builds up to higher levels over time, but many fungicide resistance mutations confer high levels of resistance so higher doses just mean stronger selection. In these cases, the appropriate dose is what is needed to control the disease; and since fungicides should be used in mixtures, the aim should be for balanced mixtures, where each fungicide is at a high enough dose to contribute to disease control so each mixing partner is protecting the other.Timing also matters: for example, with azoles, partial resistance can mean they are less effective as a curative treatment but still work well as a protectant.

This can lead to difficult decisions, as it is better to avoid a treatment altogether if disease levels will remain low, but if a treatment will be needed then it is important not to leave it until disease levels are already too high. Therefore, improved disease forecasting would help in resistance management decisions.

Theory into Practice

Finding the optimal strategy is only half the story, though, as a strategy will only work if farmers actually put it into practice. This is why it is vital that we as scientists not only get the latest advice out to farmers, but also listen to their needs so the guidelines we’re recommending are practical and economically viable on farm.

One of the biggest obstacles to optimal resistance management is the number of modes of action available. We can say that a three-spray programme should involve mixtures of two equally effective modes of action with different modes of action each time, but for the most problematic diseases we don’t have anywhere near to six different effective modes of action available. And as resistance evolves against more types of fungicide, we can end up in a vicious circle where it’s harder to protect the remaining fungicides without enough mixing partners or alternate products.

That’s why we need to look beyond chemical control- not just when the chemistry starts failing, but before we get to that point- we have some new chemistry coming in at the moment, such as QiIs for cereals, but the resistance risk is there and we need to make them last.

Beyond chemistry

In recent years, agriculture has faced increasing public and political pressures to cut pesticide use due to health and environmental concerns. At the moment some chemical crop protection is still necessary: to give sufficient disease control to produce the crop yields we need, and to protect other measures by spreading the load; for example, resistant varieties will be broken down more quickly if used alone and not in combination with a fungicide programme.

We urgently need more crop protection tools to be developed; but whether or not these tools look like a traditional fungicide spray, the risk of resistance will still be there, and the lessons we have learnt about resistance management will still apply for any new method to provide durable disease control.